Founded in 1983, The American Chestnut Foundation aims at resurrecting the blighted tree.

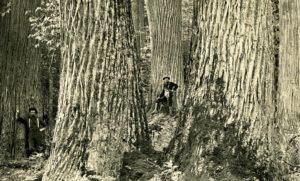

Until about a century ago, American chestnut trees dominated native forests from Maine to Mississippi. More than four billion of the noble hardwoods grew in the eastern U.S., accounting for a quarter of the trees in some areas. Thanks to its soaring 100-plus-foot height and hefty 10-plus-foot girth, the fast-growing species earned the nickname “Redwood of the East.” The wood was rot-resistant, straight-grained, and ideal for furniture, fencing, and building. The nuts fed billions of birds and animals, and Native Americans collected them to mash into a nutritious paste or to dry and grind into flour. It was the “perfect tree,” until a blight fungus—introduced by imported Japanese chestnuts—began killing it at the beginning of the 20th century. Within a few decades, the deadly disease felled nearly every tree. The chestnut blight has been called the greatest ecological disaster to strike the world’s forests in all of history.

American chestnut trees growing in Eastern U.S. in the late 19th century. (Photograph courtesy TACF.)

Although the blight has decimated it as a lumber and nut-crop species, the American chestnut has not gone extinct. Because the fungus does not kill the tree’s root system underground, the chestnut has survived by sending up stump sprouts that grow vigorously—sometimes attaining heights of up to 30 feet—and flower before inevitably succumbing to the blight and dying back to the ground. Established in 1983, the American Chestnut Foundation (TACF) is an environmental organization committed to restoring the chestnut tree to the eastern woodlands. They have instigated a breeding program in which Chinese chestnut trees, which are naturally resistant to the blight, are crossed with their American cousins. The hope is to breed blight resistance into the American tree while maintaining all its other characteristics, but progress has been slow.

An American chestnut pollination workshop at the State University of New York, College of Environmental Science and Forestry. (Photograph courtesy TACF.)

TACF’s New York chapter has supported a parallel effort to develop a genetically modified chestnut. It turned to scientists at the State University of New York who have developed a blight-tolerant tree using a gene found in wheat. The gene causes the chestnut to produce an enzyme that detoxifies the blight’s acid without killing the fungus, meaning it’s less likely that the blight will evolve ways to defeat it. And unlike the crossbred trees, the genetically engineered ones preserve nearly all of the native chestnut’s genome. To restore the species, however, scientists must introduce the blight-fighting gene into wild trees—a somewhat controversial proposition. Among the questions: Would genetically modified trees degrade the wildness of natural ecosystems, or would they bolster it by preserving species that we would otherwise drive to extinction? And who benefits—or is harmed—by their release? A fascinating Los Angeles Times article, “Should we resurrect the American chestnut tree with genetic engineering?” examines some of the conundrums, problems that will no doubt face us with increasing frequency in the coming century.

The American Chestnut Foundation

National Office

50 North Merrimon Avenue, Suite 115

Asheville, NC 28804

www.acf.org